Common Meal Timing Myths Explained

Table of Contents

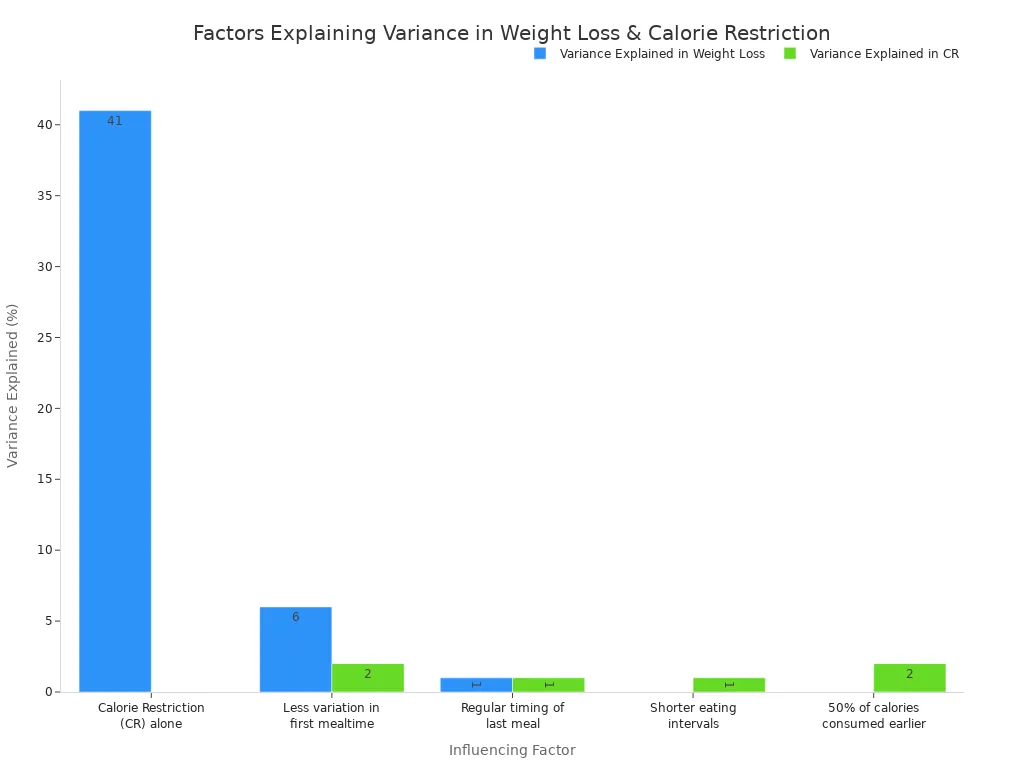

Popular nutrition advice often includes strict rules about when a person should be eating. Many of these popular rules are simply myths. For most people, total daily calorie intake, or energy balance, is the most important factor for weight management and overall health. Calorie restriction alone explains a significant portion of weight loss variance, while meal timing factors have a much smaller impact.

Common meal timing myths involve the breakfast myth, the impact of meal frequency on metabolism, late-night eating, and fears about intermittent fasting. The myth around nutrient timing and fasting often causes confusion.

The frequency of eating does correlate with total calories eaten, but this does not make frequent eating a necessity. This intermittent eating pattern can be a personal choice.

| Factor | Correlation (r) with Daily Calories | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Eating frequency | 0.44 | 0.001 |

| Time of last meal | 0.39 | 0.002 |

Debunking Common Meal Timing Myths

This section tackles some of the most persistent meal timing myths, starting with the most famous one of all: breakfast.

The Breakfast Rule

Many people grow up hearing that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. This popular belief is more of a marketing success than a scientific rule. The idea gained traction in the late 19th century, promoted by figures like Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, who advocated for grain-based morning meals for better health. This myth was further cemented by aggressive advertising campaigns that linked eating a hearty breakfast to productivity and well-being. The concept of eating three meals a day became a cultural norm, but it is not a metabolic necessity.

The Science on Skipping

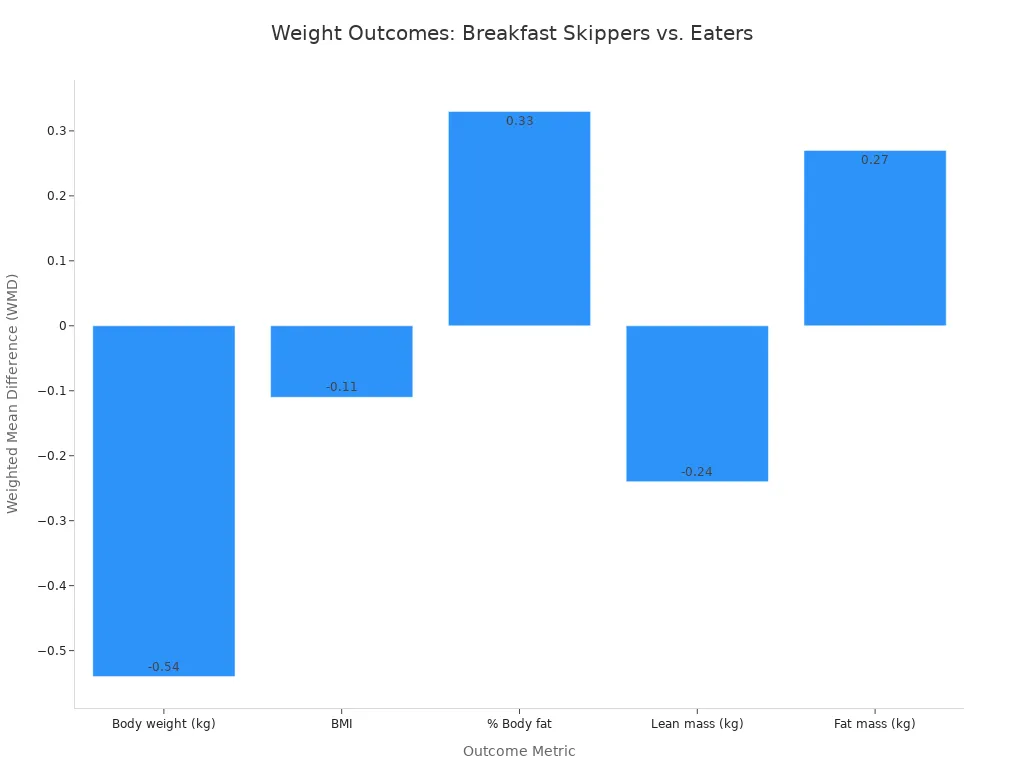

Modern science provides a more nuanced view of eating in the morning. When researchers compare people who eat breakfast to those who practice skipping breakfast, the results for weight loss are interesting.

Note: A systematic review of multiple studies found that skipping breakfast led to a slightly greater reduction in body weight compared to eating breakfast over short periods.

However, the studies found no significant differences in body fat percentage or muscle mass. This suggests that the act of eating breakfast itself is not the primary driver of weight changes.

For some groups, like children, eating breakfast can positively impact cognitive functions like attention and memory. For most adults, the decision is a matter of personal preference.

The Real Key to Weight Loss

The ultimate factor for weight loss is creating a calorie deficit. A person achieves this by consuming fewer calories than their body burns. The body then uses stored fat for energy. Whether a person accomplishes this by eating three meals a day or two is not the critical factor. An individual can successfully manage their weight by eating three meals a day or by following a different schedule. The best meal timing strategy is one that fits an individual’s lifestyle and helps them control their total daily calorie intake, moving beyond outdated myths.

The Metabolism Boost Myth

One of the most persistent meal timing myths is the idea that eating many small meals throughout the day speeds up metabolism and promotes better health. This concept suggests that frequent eating keeps the metabolic engine running at a higher rate. However, the science behind how our bodies use energy tells a different story. This particular myth often causes confusion about the best eating schedule.

The TEF Factor

The body uses energy to process the food a person is eating. This process is called the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). It refers to the increase in metabolic rate that occurs after a meal. The body burns calories while it digests, absorbs, and transports nutrients. For most people, TEF accounts for about 10% of their total daily energy expenditure. Every time a person is eating, their body uses some energy, but the amount is directly related to the size of the meal.

Meal Frequency vs. Total Calories

The core of this myth misunderstands how TEF works. Total TEF is proportional to the total calories consumed over a 24-hour period, not the meal frequency.

For example, if a person’s daily intake is 2,000 calories, their total TEF will be approximately 200 calories (10%). It does not matter if they get those 2,000 calories from three 667-calorie meals or six 333-calorie meals. The total energy used for digestion remains the same.

Therefore, increasing meal frequency does not provide a special metabolic advantage. The pattern of eating does not change the total calories burned through digestion.

The Impact on Hunger

While a higher meal frequency does not boost metabolism, it can influence hunger levels. Some people believe that frequent eating helps control appetite, but research suggests the opposite can be true. A study that compared eating three large meals to six small meals, with identical total calories, found no difference in fat loss. Interestingly, the participants with a higher meal frequency reported feeling hungrier and having a greater desire for eating. This shows that a lower meal frequency may be more effective for appetite control for some individuals. The best meal timing is one that helps a person manage hunger and control their total eating.

The Muscle Loss Myth

A common fear in the fitness world is that going more than a few hours without eating will cause the body to enter a “catabolic” state and break down precious muscle for energy. This belief drives the idea that one must be constantly eating to preserve gains. However, this is one of the most persistent myths about nutrient timing. The body is far more resilient than this myth suggests.

How Your Body Uses Protein

Your body has a sophisticated process for using the protein you get from eating. When a person is eating protein, it triggers a process called Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS). This is how the body builds and repairs muscle tissue.

- Dietary protein provides amino acids.

- These amino acids travel to the muscles.

- They are then used to build new muscle proteins.

- This process peaks around 90 minutes after eating and then returns to normal, even if amino acids are still available.

This temporary response is called the “muscle-full” effect. While MPS is often maximized with around 20-25 grams of protein, the body can effectively use larger amounts from a single meal for tissue building. This shows that constant eating is not necessary to stimulate muscle growth.

The Myth of Catabolism

The idea that your body immediately starts eating muscle for fuel after a few hours is a myth. During the first 24 to 48 hours of fasting, the body primarily uses stored fat for energy. While there is a small, temporary increase in muscle protein breakdown in the first few days of a prolonged fast, the body quickly adapts. It enters a protein-sparing state, significantly reducing its reliance on muscle for fuel. For someone simply going 5 or 6 hours between meals, the body has plenty of other energy sources to use before it considers breaking down significant muscle tissue.

What Truly Preserves Muscle

Instead of worrying about meal timing, two factors are far more important for preserving muscle: total protein intake and resistance training. For good health and muscle maintenance, especially during weight loss, focusing on these is key.

Tip: Studies show that a daily protein target of around 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight is highly effective for preserving muscle.

- In one study, a group eating low protein lost about 1.6 kg of muscle, while a high-protein group lost only 0.3 kg.

- Resistance exercise, like lifting weights, sends a powerful signal to the body to hold onto muscle mass, even during a calorie deficit.

Ultimately, consistent training and sufficient daily protein from eating are what protect muscle, not a rigid eating schedule.

Late-Night Eating and Meal Timing

One of the most common meal timing myths is that eating late at night automatically leads to weight gain. This idea suggests the body handles calories differently after a certain hour. However, the principles of energy balance apply over a 24-hour cycle, making the timing of eating less important than the total amount.

A Calorie is a Calorie

The human body operates on the laws of thermodynamics. Your body’s internal energy changes based on the food you consume versus the energy you use. This concept is known as energy balance. Eating food adds chemical potential energy to your system. Your metabolism then converts this energy for bodily functions.

If a person’s food intake equals their energy output from daily activities, their internal energy remains constant. A positive energy balance, where a person is eating more calories than they burn, leads to the storage of extra energy as fat. This process is not dependent on the clock. A calorie surplus will disrupt energy balance whether it occurs at 8 AM or 8 PM.

The Late-Night Snack Problem

The real issue with late-night eating is often the food choices people make. The problem is not the time itself but the type and amount of food consumed. People often reach for convenient, high-calorie snacks before bed. This mindless eating can easily push a person into a calorie surplus.

- A small serving of trail mix can contain over 170 calories.

- A handful of pumpkin seeds adds another 158 calories.

These snacks quickly add up, making it difficult to maintain a healthy energy balance. This pattern, not the act of eating at night, is what contributes to weight gain. Focusing on balanced meals throughout the day can prevent this.

When Night Eating Can Help

For some individuals, especially athletes, eating before bed can be a smart strategy for health and performance. This is a key aspect of nutrient timing. Research shows that a protein-rich meal before sleep can significantly improve muscle recovery.

Studies demonstrate that consuming around 40 grams of protein before sleep stimulates muscle protein synthesis overnight. This process helps repair and build muscle tissue after exercise. For those engaged in resistance training, this form of eating can enhance gains in both muscle mass and strength. This shows that the late-night eating myth has exceptions and that a strategic approach to meal timing can be beneficial.

Intermittent Fasting and “Starvation Mode”

A common myth suggests that intermittent fasting puts the body into “starvation mode,” slowing metabolism and hindering weight loss. This fear often stops people from trying time-restricted eating patterns like eating only one meal a day. However, this idea confuses the body’s response to short-term, intermittent fasting with its reaction to chronic starvation. The practice of intermittent fasting involves cycles of eating and fasting, which is very different from constant deprivation. This intermittent schedule, such as eating one meal a day, does not trigger the same metabolic alarms.

Defining Starvation Mode

True “starvation mode” is a clinical concept called adaptive thermogenesis. It is a real metabolic process.

This is a survival mechanism for long-term famine, not a response to skipping a meal or following a time-restricted eating plan like one meal a day. The intermittent fasting approach of eating one meal a day does not create this sustained deficit.

Short-Term Fasting’s Effect

Short-term fasting, a key part of intermittent fasting, affects the body differently than chronic deprivation. Research on its effect on metabolic rate is mixed. Some studies show a brief increase in energy use during the first few days of fasting. This may be due to hormonal changes. The benefits of this eating style are notable. For instance, short-term fasting can:

- Enhance the secretion of human growth hormone.

- Increase levels of norepinephrine, a hormone that helps mobilize fat for energy.

These hormonal benefits can support weight loss goals. The body’s response to intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating is complex. An intermittent schedule like eating one meal a day can offer unique benefits. This type of eating is a popular form of time-restricted eating. The intermittent fasting approach of eating one meal a day is a valid strategy.

Fasting vs. Chronic Deprivation

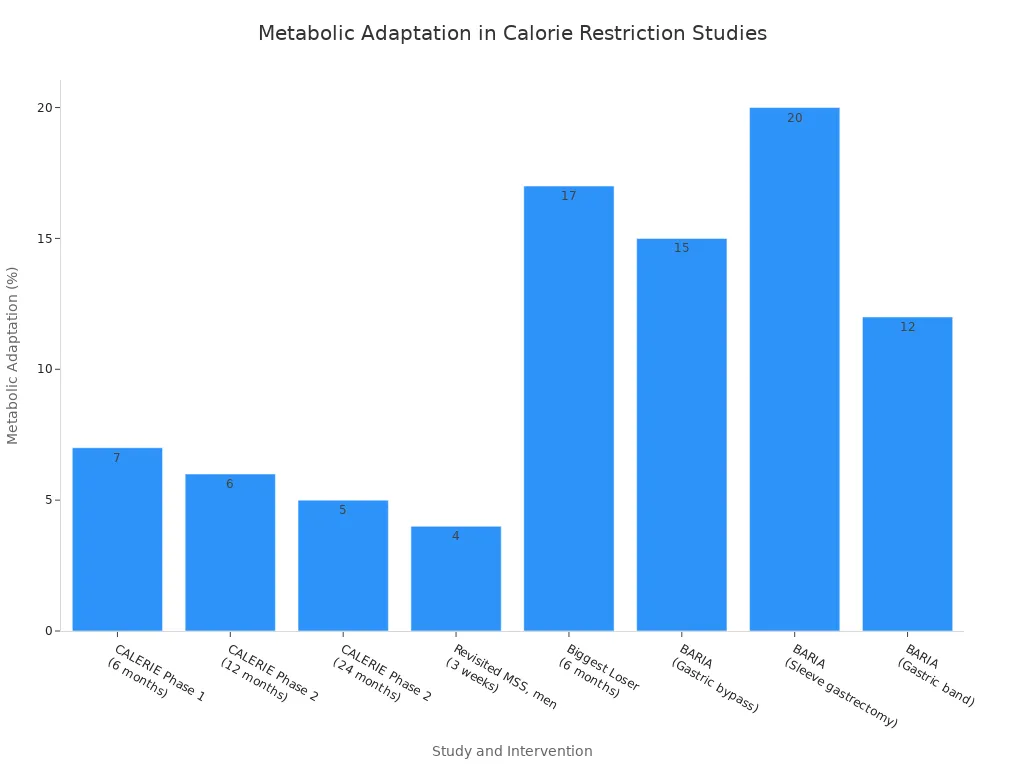

The key difference is duration. The metabolic slowdown seen in “starvation mode” occurs with chronic, severe calorie restriction over many months. An intermittent fasting schedule, such as time-restricted eating or eating one meal a day, does not create this condition. The daily cycle of eating and fasting is not long enough to trigger this adaptive response.

Studies show that significant metabolic adaptation happens with long-term dieting. For example, a two-year study found that people with a 15% calorie restriction had an energy expenditure 80-120 calories lower per day than predicted. This shows how the body adapts to prolonged low-calorie eating for better health and survival. The intermittent fasting approach of eating one meal a day avoids this. This is a key difference between intermittent fasting and chronic dieting for weight loss.

| Study Type | Duration | Calorie Restriction Level | Metabolic Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CALERIE Phase 2 | 24 months | 25% CR | 5% |

| Biggest Loser | 6 months | Diet & exercise | 17% |

| BARIA | 24 months | Sleeve gastrectomy | 20% |

This data highlights that the body’s response to a meal timing strategy like intermittent, time-restricted eating (e.g., one meal a day) is fundamentally different from its response to long-term deprivation.

Other Quick-Fire Myths

Beyond the major myths, several smaller beliefs about meal timing persist. These quick-fire myths often concern the relationship between eating and physical activity. This section will clarify the facts.

Exercise and Digestion Myths

A common myth suggests people must avoid all exercise after eating. This idea is not entirely accurate. Performing light activity immediately after eating can be beneficial. It helps lower post-meal glucose levels. This effect occurs whether a person has type 2 diabetes or not. The body’s response after eating is better with immediate activity. The period of fasting before the next meal begins with better glucose control. This is different from prolonged fasting. The eating and activity cycle is important.

For intense workouts, timing becomes more relevant. Experts recommend eating a complete meal two to three hours before intense exercise. This gives the body time for digestion. A smaller meal focused on carbs and protein requires less time. A person can have this type of eating about one to 1.5 hours before training. This strategic eating fuels performance without discomfort. This is not the same as the fasting state. The body uses the energy from eating. This is unlike fasting. Fasting requires different energy strategies. Fasting is not the goal here.

Resting for Digestion

The belief that a person must rest completely after eating is one of the popular myths. While a large meal might make a person feel sluggish, total inactivity is not necessary. The body can handle light movement perfectly well after eating.

Tip: A short, gentle walk after a meal can aid digestion for some individuals. It is a better choice than lying down immediately after eating.

This approach to meal timing helps manage energy levels. It avoids the discomfort that can come from exercising too hard after eating. The body is not in a fasting state. It is actively processing the food from eating. This is a key difference from fasting. The body’s needs during fasting are different. The body’s needs after eating are different. Fasting and eating create distinct metabolic states. Fasting is a state of not eating.

Ultimately, many popular meal timing myths are just myths. A person’s total daily nutrition is more important for health than a rigid eating schedule. A flexible meal timing approach is a better weight control strategy. This eating focuses on nutrient timing. This eating is not about fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting, fasting. This eating, eating, eating, eating, eating, eating, eating, eating, eating is about smart nutrient timing. The optimal meal timing plan supports this nutrient timing, nutrient timing, and nutrient timing.

FAQ

What is more important than meal timing for weight loss?

Total daily calorie intake is the most critical factor. A person loses weight by creating a calorie deficit. The specific timing of eating matters less than the total amount of food consumed over a 24-hour period.

Does eating small, frequent meals boost metabolism?

No, this is a common myth. The body’s energy use for digestion depends on total calories, not meal frequency. Eating six small meals or three large meals with the same total calories results in the same metabolic effect.

Will I lose muscle if I don’t eat every few hours?

No, the body does not immediately break down muscle. It primarily uses stored fat for energy between meals. Consistent resistance training and adequate daily protein intake are the most effective ways to preserve muscle mass.

Is eating late at night bad for you?

The time itself is not the problem. Weight gain often comes from the high-calorie snacks people choose late at night. A calorie surplus causes weight gain regardless of the time. Strategic eating before bed can even help muscle recovery.

Poseidon

Master of Nutritional Epidemiology, University of Copenhagen, Herbal Functional Nutrition Researcher

Focus: The scientific application of natural active ingredients such as Tongo Ali, Horny Goat Weed, and Maca to sexual health and metabolic regulation.

Core Focus:

Men: Use a combination of Tongo Ali (an energizing factor) + Maca (an energy reserve) to improve low energy and fluctuating libido.

Women: Use a combination of Horny Goat Weed (a gentle regulator) + Maca (a nutritional synergist) to alleviate low libido and hormonal imbalances.

Stressed/Middle-Aged Adults: This triple-ingredient synergy supports metabolism, physical strength, and intimacy.

Product Concept:

Based on traditional applications and modern research (e.g., Tongo Ali promotes testosterone-enhancing enzyme activity, and icariin provides gentle regulation), we preserve core active ingredients and eschew conceptual packaging—using natural ingredients to address specific needs.

Simply put: I'm a nutritionist who understands "herbal actives." I use scientifically proven ingredients like Tongo Ali, Epimedium, and Maca to help you make "sexual health" and "nutritional support" a daily routine.